Scientists Have A Plan For Growing Food On The Moon. Here's What It Looks Like

Space agencies like NASA are busy planning to send humans back to the moon. And in the long term, they don't want people to visit just for a few days. The plan is for astronauts to stay on the moon for weeks or even months at a time, allowing them to perform more complex research. But if we want people to be able to live on the moon for longer periods, we need to find ways to meet their resource needs.

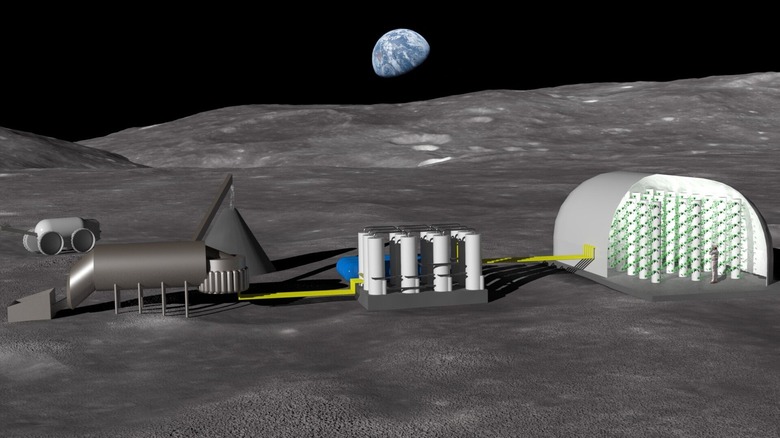

Carrying all of the food required for a long mission to the moon would be expensive and difficult, so one idea is for astronauts to grow their crops there. Several space agencies and private companies are researching how to grow food on the moon, and one day soon there could be veggie gardens and more on the lunar surface.

One such research project is being done by a Norwegian company called Solsys Mining who are working with the European Space Agency (ESA) to find ways to grow plants on the lunar surface.

"This work is essential for future long-term lunar exploration," said Malgorzata Holynska, a materials and processes engineer at ESA. "Achieving a sustainable presence on the Moon will involve using local resources and gaining access to nutrients present in lunar regolith with the potential to help cultivate plants."

The problem of lunar regolith

The moon doesn't have soil like Earth. The dusty material which covers its surface is called regolith. This regolith has some different properties from soil — for example, it has no bacteria or other living matter, and it has less nitrogen in it. Both of these are problems for growing plants as they need nitrogen to grow and life in the soil like worms help to aerate it. Regolith also reacts differently to water than soil, as it tends to compact down instead of absorbing it.

That's why many suggestions for growing crops on the moon have suggested using a hydroponic system, in which plants are grown in a nutrient-filled water instead of soil, so they don't actually come into contact with the regolith.

But it would be more efficient to find a way to use the moon's regolith, rather than carrying all of the materials required for hydroponics. The Solsys Mining system uses a mechanical sorting system and a chemical processing section, so the regolith passes through a series of processes which extract the needed nutrients from it. The extracted nutrients are then turned into a fertilizer which can be used in a hydroponic system.

This way, regolith can be processed and the useful nutrients extracted from it, so the plants can grow in the hydroponic system and be fed by the fertilizer made from the readily available regolith.

Growing plants in the regolith

An alternative approach is being pursued by NASA. Its study is looking at growing plants in the regolith itself. Researchers were able to cultivate a hardy plant called Arabidopsis thaliana in lunar regolith. The plants weren't as hardy when grown in regolith as they are when grow in soil, but they were able to grow.

The researchers grew the plants in real samples of regolith collected in the Apollo 11, 12, and 17 missions. This is a very precious resource, so the researchers used just one gram of regolith for each plant, to which they added water and a seed. To the researchers' surprise, the plants began to sprout within a few days.

However, the plants weren't as healthy as they should be, with stunted leaves and roots. The researchers also found that plants grew better in some samples than others, suggesting that regolith from different areas of the moon might be more or less suitable for growing plants. The researchers are now working on learning more about how to adapt plants to be able to grow in these difficult conditions.

"To explore further and to learn about the solar system we live in, we need to take advantage of what's on the Moon, so we don't have to take all of it with us," said Jacob Bleacher, the Chief Exploration Scientist supporting NASA's Artemis program. "What's more, growing plants is the kind of thing we'll study when we go. So, these studies on the ground lay the path to expand that research by the next humans on the Moon."